What you need to know:

- Kenyatta possessed a unique quality. His birthdate remained unknown to most individuals, just like his classmates remained a mystery to many.

- Very few individuals were aware of Kenyatta’s educational institution. All that was known about him was that he was a resilient individual who had pursued his education in Britain.

For over 24 years, Kenyans were confronted by a stern countenance. His image adorned the walls of offices and shops, graced every banknote and coin, and remained a constant presence in our daily news broadcasts. His gaze appeared to convey a message: “Do not challenge the leader, for I am omnipresent.” The leader in question was Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, the former President of Kenya.

HISTORY

An unexpected phone call spurred me into action, embarking on a comprehensive research journey for a four-part series. This undertaking involved delving into Kenya’s rich history and comprehending the political developments that transpired under the administrations of both Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi.

Despite considering myself knowledgeable about our country’s history and the events that unfolded over the past five decades, I swiftly discovered that there was an abundance of information that surpassed the collective awareness of any Kenyan regarding these two eminent figures. Motivated by this realization, I made the decision to undertake a captivating expedition, aiming to uncover intriguing details about the personal habits, obsessions, and intimate moments of our former presidents. Above all, my intention was to narrate the life story and experiences of an individual who tirelessly served alongside two of Kenya’s most influential leaders throughout the course of their historical reigns.

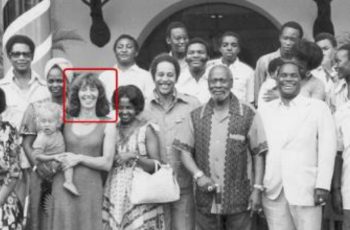

Furthermore, I uncovered the profound connection between my own father and the history of our nation, realizing how harmoniously the photographs he captured aligned with this remarkable narrative.

Come along on an exclusive journey through a captivating four-part series titled “A Life Behind the Scenes” featuring Mr. Lee Njiru.

SALIM: What made you choose me to be the one to make that phone call, expressing your desire to share your story?

NJIRU: I had the privilege of knowing your late father, Mohamed Amin. He was not only a skilled photographer and cinematographer, but also a dear friend of mine—a man of integrity.

I recall a particular incident that remains vividly imprinted in my memory. We were covering Mzee Jomo Kenyatta during a mini Cabinet reshuffle, and due to the limited space in our small car, we were quite cramped. Consequently, we placed the film on the rack. Unfortunately, somewhere along the journey, it slipped off, resulting in the film being exposed. This was no trivial matter, as Kenyatta was not one to be taken lightly; he could bring about dire consequences. We found ourselves wondering, “What should we do?” We devised a plan to visit the nearest pharmacy, purchase bandages and red ink, and then stage a fake car accident, pretending to be injured like donkeys. Our intention was to approach Kenyatta and inform him of the mishap, proposing that we redo the entire event. However, just as we were about to enact our scheme and roll the car, we spotted a large vehicle with flashing lights approaching at high speed—it was your father. He questioned me, “Are you truly a friend? Did you know about this reshuffle? What am I supposed to tell my superiors in London?”

FRIENDS

I assured him, saying, “No need to worry, we will ensure you reach your destination.”

Thus, we proceeded. We encountered Kenyatta’s bodyguard, whose name was Kimotho. We conveyed to him, “What we have captured can only be showcased within Kenya. However, what Mohamed Amin will capture will be broadcasted worldwide.” Kenyatta was summoned, and he inquired, “Will it be seen even in Europe?” We affirmed, saying, “Yes, sir. The entire world, Your Excellency.” Following that, he instructed us, “Come on, bring forth that speech of mine.”

Therefore, we rearranged our plans, and Kenyatta inquired, “But what are you all taking?” We responded, “No, sir, we are simply assisting Mohamed.” Subsequently, to avoid any further mishaps, we took it upon ourselves to diligently safeguard the film. We were determined not to allow a repetition of the previous incident. From that point forward, your father and I forged a strong friendship.

EMERGENCY

I came into this world in 1949, in a humble village named Mbiruri, with the closest town being Runyenjes. My birth coincided with an exceptionally challenging period. When I was around four years old, a State of Emergency was declared. In 1950, there was a significant surge in demands for independence, leading the British to implement what they referred to as ‘The Scorched Earth Policy.’

We found ourselves completely isolated, devoid of any means of communication. There was no contact with our wives, children, or even our sympathizers anywhere.

DENIGRATED

Therefore, those were the conditions in which I grew up: devoid of food, lacking access to medical care, and in a state of constant unrest. My people faced denigration and insults. Merely identifying as a Muembu carried a perception of insignificance and irrelevance. This is precisely why I dedicated myself to working tirelessly, so that the Embu people could gain recognition in Kenya. Particularly during that era, there was an absurd practice of referring to certain groups of people in derogatory and demeaning terms. For instance, if someone belonged to the Taita community, they would be called ‘Kamutaita’. Regardless of being a person of considerable stature, they would still be referred to with insolent terms such as ‘Kamutaita’ or ‘Kamujaluo’.

MEGAPHONES

On April 24, 1954, Nairobi became encircled by approximately 25,000 British soldiers. They employed megaphones to instruct all men to exit their homes while carrying whatever belongings they could manage. If you happened to be Kikuyu, Embu, or Meru, you were subjected to beatings as you were required to present your identification papers. Consequently, those individuals were apprehended and transported to detention centers like Lang’ata, Manyani, Hola, and others. Conversely, if you belonged to the Luo, Kamba, or any other tribe, you were released and instructed to return home. This marked the commencement of the persecution of anyone suspected of having ties to the Mau Mau movement.

Irrespective of the circumstances, being a Kikuyu, Embu, or Meru man automatically classified you as Mau Mau, whether actively involved or passively associated. That label, Mau Mau, was assigned to individuals from these communities. They endured immense suffering, with many losing their lives in the process.

Tragically, some individuals experienced horrific atrocities, including castration, fatal beatings, mutilations, and the onset of madness. To this day, there are individuals who continue to bear the physical and emotional scars inflicted upon them during that time.

PROSTITUTES

The desire for independence drove people to resort to violence. The catalyst for this shift in approach can be traced back to the Second World War, which commenced in 1939. During the war, numerous Kenyans joined the fight in places like Burma, Malaysia (then known as Malay), and North Africa. These experiences exposed them to a different reality. For many, it was their first encounter with deceased Europeans, European prostitutes, sick Europeans, mentally unstable Europeans, and European beggars. Witnessing these previously unseen aspects of European life had a profound impact. It opened their eyes to the vulnerability of Europeans and shattered the perception of their invincibility. The realization dawned that instilling fear in the Europeans was the key to driving them out of Kenya. Consequently, people began forming alliances, taking oaths, and engaging in forest-based resistance, fighting for their cause.

CLASSMATES

By approximately 1955, when I was merely six years old, I began to hear mentions of prominent figures such as Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi, and Oginga Odinga. However, Kenyatta held a distinct position among them. Very few individuals were privy to details about his birth, his classmates, or the specific educational institutions he attended.

DETENTION

The limited knowledge available about Kenyatta conveyed that he was a resilient individual who had traveled to Britain and Russia. It was believed that he possessed knowledge in psychology and had the ability to discern people’s thoughts. There even circulated a myth that he had a hairy tongue.

I recall a significant event in 1959 when Mzee Moi, Henry Cheboiwo, and others visited Kenyatta while he was in detention. They held a firm belief that Kenyatta would eventually become President. In anticipation of his release, Moi and his friends made arrangements to purchase a car for him. They acquired a vehicle with the registration number KHA, representing ‘Kenyatta Home Again.’

INTELLECTUAL

During the 1960s, I became acquainted with the name Tom Mboya. He stood out as a highly charismatic leader, known for his smooth and skillful political maneuvers. It seemed that Kenyatta held a favorable opinion of him, appreciating his hardworking nature and intellectual prowess. However, among the Kikuyu community, Mboya’s intelligence and cleverness made him somewhat unpopular.

BRAINWASHED

Before Kenyatta’s release from detention, there was an incident where Mboya was in Canada. When asked about who would become Kenya’s President, Mboya responded by saying, “Kenyans will decide.” This statement was noticed by the Kikuyu community. They desired a clear and definitive answer, specifically in favor of Kenyatta. People speculated that Mboya could potentially be Kenyatta’s successor. However, the Embu people did not share the same concern since they perceived Mboya as a Luo. At that time, there was a prevailing belief that leadership should remain within the Mt Kenya region. As young individuals, we had been influenced by the narrative that a Luo should not lead the country. Remarkably, this narrative persists to this day.

SALIM: So you were not fully aware of the repercussions?

NJIRU: No, I did not comprehend the full extent of the consequences. It was a Luo individual who had been killed. Interestingly, Mboya was not universally adored even among the Luo community, as he himself was not ethnically Luo. Mboya belonged to the Bantu group, specifically the Basuba from Rusinga Island, which is distinct from the Luo ethnicity. However, due to the numerical strength of the Luo community, the Basubas adopted the Luo language, Dholuo, for their own survival since they could not sustain themselves solely as Basubas.

SALIM: It appeared apparent that the assassin was a Kikuyu, but was it truly that straightforward?

NJIRU: I was quite intrigued to uncover more details, but unfortunately, the information regarding the matter is scarce. Our only sources are the newspapers. As for Nahashon Njenga, the presumed killer, all we know is that he mentioned, “Why don’t you ask the big man?” However, we remain unaware of the identity of this “big man.” No further information has ever been documented beyond that point. Despite my attempts to conduct research and gather relevant materials, there is simply no information available. Even the whereabouts of Nahashon Njenga remain unknown to this day.

SALIM: You mentioned that Kenyatta held a great deal of admiration for Mboya, and it was evident that they had a strong bond and got along well. They were indeed good friends. However, it is possible that it did not serve the interests of certain individuals for Mboya to ascend to such a position of power.

NJIRU: Yes, indeed, there were forces that opposed such a scenario. As you recall, even Moi faced resistance in his bid to become President. There was a prominent group called “Change the Constitution” that actively worked against Moi’s presidency. This is a well-known fact.

JOURNALISM

In reality, I only truly understood the significance of freedom much later, much later indeed. Back then, even if I faced insults from Europeans, it didn’t bother me much as it was simply a way of life. Even today, many individuals believe that true independence has not been achieved. Why? It is because those who took up arms and fought in the bush feel that they were not given a fair and just outcome.

The ones who profited were the home guards and individuals with privileged access to education. It was the sons of colonial chiefs and loyalists who reaped the rewards, obtaining positions as permanent secretaries and high commissioners. These individuals, in essence, enjoyed the prime benefits of independence.

DISENCHANTED

Even to this day, there is a prevailing sense of disillusionment among many people who believe they were treated unfairly. Consequently, they perceive that independence was not meant for everyone…

A significant portion of our society continues to harbor deep anger and resentment, strongly believing that they were subjected to unjust treatment. These feelings persist among the people to this day.